| You know what’s crazy? I’ll tell you what’s crazy.™

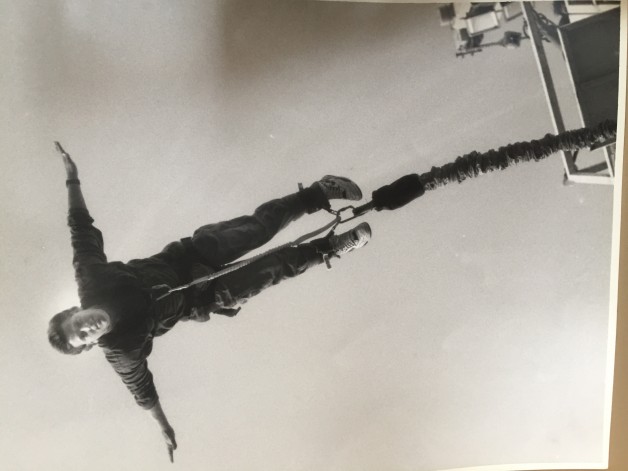

24 years in Nashville. February marks my 24th year at WKRN. Man how time flies when you’re having fun. I’ve spent the last 24 years in Music City at WKRN. I remember Nashville before cranes littered the skyline, twirling over buildings like steel ballerinas. I remember when I covered JUST SAY NO to bringing the Titans to town. I remember when Lower Broad wasn’t a conveyor belt of drunken tourists and ubiquitous 3 story Honky Tonks. I remember a broadcasting world before iphones and social media when you had to pay your dues in smaller markets before coming to a gem of a city like Nashville. I paid those dues all over the country. I worked 8 years and 3 cities as a reporter before I even got my job in Nashville. Most of that time was spent as a one man band. I carried my own camera and tripod and record deck. The gear must have weighed 80 pounds. I ruined a million shirts and often looked like a sweaty swamp rat on TV while trying to get the story. As I reminisce on my time in Middle Tennessee, I realize that I’ve been in the broadcasting business for close to 42 years. That includes college internships and part time jobs at KTLA and KABC in L.A. Like a Labrador Retriever puppy that just knows how to chase a ball, I think I was always destined to chase news. I started broadcasting when I was 16 years old. My high school had a 15 watt radio station that expanded to 100 watts by my senior year. I was a disc jockey on Saturday mornings for 3 hours playing Ted Nugent and AC/DC and U.F.O. I eventually became the sports director and by the time I graduated, I literally had hundreds of hours on air broadcasting football games on Saturdays and at least 2 basketball games a week. My first regular on air reporting job began in 1988. My demo tape was loaded with sportscasting. My 1st boss, Jim Hale said, “Son, I like your enthusiasm, but we don’t have any sports openings. You think you can do news?” “OF COURSE!” I told him. I FIBBED. I really had no idea what the news universe looked like. I was a sports guy. I knew 3 pointers and Hail Mary’s. I didn’t know an affidavit from a 2 car head on. I went to the Library and got a book on Idaho. Remember, there was no internet machine back in the day. Gem State. Potatoes. Cold. Skiing. I was young and dumb and ready to chase a dream. One day I was in Redondo Beach, California, watching porpoise surf the waves beyond the Esplanade. The next day I was on I-15 driving North, into a white out so thick, I couldn’t tell where the asphalt ended and the avalanche zone of death began. Idaho Falls, Idaho was market 165. For comparison, New York is 1. L.A. is 2. Chicago is 3. Back then Nashville was like 31. Jim Hale told me that I would be the bureau chief for the station. I didn’t know what that meant, but it seemed important. I would come to learn that it meant that I was responsible for anything that happened outside Pocatello, where all the other reporters worked. If there was a potato truck over turned anywhere, in Eastern Idaho, Wyoming or Montana, that was my beat. There was no formal training. Some guy handed me my equipment and said, “you white balance your camera by pointing it at the snow and making sure your video ain’t blue.” “Why at the snow?, I asked. Because there’s always snow and it’s always white he responded with a laugh. Then he left and I was on my own to learn. It was like that scene in 2001 A SPACE ODYSSEY where the monkeys touch the celestial monolith of enlightenment. So I touched the news monolith and my quest for the truth began. I was so raw, so dumb. But I burned to get better. I shot a lot of blue video those first few weeks. I did more than a few stand ups where the camera moved without my knowledge and I was left with a talking shoulder. The winter I moved to Idaho was one of the coldest on record. I was a California boy who lived at the beach. I thought 60 degrees on a foggy night was borderline unbearable. Idaho is still the great frontier. It’s wild rivers and expansive forests. It’s peregrine rivers and fields of golden glory. Idaho is the place where Eagles soar through pristine skies where Americans dare to be free. Idaho is the stop on the trail west where settlers in their covered wagons take one look at the peaks of the Grand Tetons and say, “Ma, we can’t cross that. We’re home!” Idaho winters are created in the laboratory of primordial elements. The savage cold is super charged in the mountains above Driggs and then it funnels like an icy fist to the solar plexes across the plains below. Cold is relative. In California it’s a sweater on a cool night on the pier. In Idaho, it’s 7 layers of gortex and a snorkel hood that makes everything you see seem like it’s coming at you through a porthole on a frozen submarine. How cold was it? It was so cold that animal heads snapped off their bodies. Swans have long, fragile necks. And during this winter, the bird’s necks, like brittle candy canes cracked and separated from their bodies. I remember doing a stand up, holding two frozen swan heads, to show viewers something they had likely never seen. “Hey Eastern Idaho! You think it was cold? At least your head didn’t fall off.” How cold was it? The tires on my news vehicle cracked. The rubber actually split. The only reason the engine block didn’t freeze over is because in Idaho, you plug your car into the electrical grid at night to keep a warm current of energy flowing across the metal. I got a twinge of frostbite that bothers me to this day, in Idaho. How cold was it? I was covering a blizzard in the middle of nowhere. A rancher had reportedly lost a 1,000 head of cattle overnight. I was in an Army National Guard helicopter flying over the barren tundra. The door was open and the icy wind mixed with the heaters inside the chopper. It was a violent collision of energy and noise all accentuated by white as far as the eye could see. After 30 minutes of flying, the chopper banked and floated over a white void. I motioned to the soldier beside me, screaming, “Where’s the herd?” It was so loud the soldier only pointed to the white emptiness below. My viewfinder was black and white. The zebra pattern in the lens was creating an optical illusion that made it difficult to see anything. But as I zoomed in, I soon understood. Suddenly, my little black and white viewfinder was filled with hooves and horns and frozen heads just poking through the snow. Below me, in a massive frozen assault of snow and ice was the remnants of 1,000 dead cows. The animals literally froze to death, in their tracks, side by side. Then they were buried in a casket of pure white in a serene tomb that must have been 7 feet high. As we hovered over this atrocity, I couldn’t help but think that I was gazing down upon a prehistoric cathedral of death, the full extent of which we would see, only when the thaw came days later. I told many stories at this ranch. The herd was obliterated over night by a winter blast that fell like a blacksmith’s hammer on an anvil of unforgiving ice. I remember talking to the teary eyed rancher. The night before the cattle apocalypse, he was a wealthy man, his ranch one of the dominant businesses in the state. Over night, in a calamity that only comes around once in a generation, he was cow-less, humbled, stunned. But America is a wonderful place where citizens always step up to help. By the time the last of the rancher’s cows was removed from the icy bog, the cattle industry was in full swing taking care of one of their own. When my story of cow-cicles made it to the network, Cattle Ranchers rallied. Within days cows started pouring in to Eastern Idaho. A rancher in Nebraska put two cows in a trailer and sent them west. A rancher in Wyoming put 3 cows on a trailer and sent them South. Cows came from Texas, from Arizona, from Wisconsin. Within days, the Eastern Idaho Rancher who went from a 1,000 cows to zero cows, suddenly had hundreds of cows. I can’t remember if his lost herd were Black Angus or Holsteins. That no longer mattered. Now he was the Benetton of Cows. He suddenly was the recipient of cattle charity that included brown cows and white cows and black cows and spotted cows and milk cows and beef cows and boy cows and girl cows. The rancher’s cattle, filling his pens every day, looked like a rainbow of mismatched shoes in a gigantic muddy closet. He had cows of every type. The rancher was humble and filled with gratitude. America can be good that way. From Idaho, I moved across the country to the Atlantic Ocean. I hitched my car to the back of a U Haul and traveled over the Rocky Mountains. I drove across the prairies on the other side of the continental divide. I remember seeing the arch and the mighty Mississippi. I drove through Nashville thinking it looked like a cool city that I’d one day like to visit, but doubted I ever would on this unpredictable news venture. 3 days later I was Greenville, N.C. Home of the ECU Pirates and the best news I had covered up to this point in my career. Greenville, and Kinston and New Bern and Jacksonville. This is where I really learned to hone my craft as a crime reporter and story teller. If Idaho was a battle of the elements. Eastern North Carolina was a showcase in savagery. I covered crimes so horrific they took your breath away and made you question the meaning of life. I was one of the first on scene at the Be-lo Grocery Store massacre in 1993. A knife wielding psychopath stacked bodies on top of one another. The murderer tied the victims with duct tape, and then he stabbed the workers so ferociously that his knife broke off in some of their bodies. I remember police telling me that he dragged the corpses around the aisles, leaving a slimy blood trail. This horrific act is still unsolved as far as I know. And this is just one of countless despicable scenes I covered while living a stone’s throw from the Outer Banks, one of God’s finest geological achievements. In the early 90’s, Eastern North Carolina was a small market with a big crime problem. I was still a one man band, shooting, writing, editing my own stories. It’s here that I developed my array of police contacts who filled my morning coffee pot with a plethora of gruesome options. When the days were slow, or I was bored, I would often ride around with the crime suppression team of the Greenville Police Dept. I became fast friends with a sagacious street cop named C.J. Hardy who had a long scar across his cheek. It was a knife fight that he won as a younger man. Hardy was the kind of cop who could have gone either way growing up. He could’ve been a hoodlum, working the streets, pushing the dope. But instead he chose the light. He chose to wear a badge and lock up the bad guys. He understood the criminal mind and that’s what made him one of the best cops I ever knew. I’d often ride with him around West 5th street. Back in the day, this was the worst part of town. This is where crack was king and drive by shootings were a regular rhythm of the night. I covered many a hurricane, political upheavals, and somewhere there’s a child, now all grown up, whose middle name is Cordan. Yep, his momma wrote me once and said she gave her baby boy the middle name Cordan because she liked the way I reported. Unusual, but still sort of cool, I think. I made a lot of friends in this coastal community, many of whom I still communicate with to this day. And perhaps most importantly, I started to develop a style of reporting that would serve me well for decades to come. Eastern North Carolina is a military community. Camp Lejeune and Marine Corps Air Station at Cherry Point and Seymour Johnson Air Force Base. It was here that I also learned to cover the military and appreciate their special place in the fabric of our American Quilt. In 1990, I flew with the Air Force to Rihad, Saudi Arabia. I was covering our troops in Operation Desert Shield, just prior to our invasion of Iraq. We flew over on a KC-10, which is essentially a big gasoline station with wings. The back of the cargo hold was filled with crates of supplies. I remember sleeping on a pallet of MRE’s while crossing the Atlantic. One of my most profound memories was a sliver in time over Egypt. I was standing with the refueling crew in a glass box positioned underneath the plane. Below us, I watched an F-15 E Strike Eagle soar into position. The attendant slowly lowered the air refueling hose that connected to the jet. In those moments, while jet fuel flowed from one plane to another in a technological marvel that is still baffling to this day, I found myself waving to the jet pilot only 20 feet below. I could see in his cockpit. I could see the reflection of the clouds in his face shield. I remember him waving at us. But perhaps the burning bush of memories is the visage beyond his cockpit, under his wings. As we soared across this ancient land, directly under his plane, I saw the unmistakable Pyramids of Egypt. That moment was biblical meets technological superiority in a single bat of an eye. From Eastern North Carolina, it was off to Grand Rapids Michigan. I learned to love my time in Idaho. I skiied at Grand Targee and Jackson Hole. I loved my time in North Carolina where my rival reporters were also my best friends where we’d spend many a Saturday afternoon on the white sands of Atlantic Beach. While Michigan is also beautiful in its own way, it was never really my cup of tea. Perhaps it was the onslaught winters that simply erased spring and fall from the calendar. Perhaps it was the night shift in Grand Rapids that wore me down. I will never forget the first time I gazed upon Lake Michigan and thought that I was back at the Atlantic. From the beaches of Holland, Michigan, with the light houses and sand and white caps before you, you’d swear you were looking at an ocean. I met some great people, told a few good stories, and made a bunch of road trips to Chicago. But in the end, it was too much cold and not enough change of seasons for me. In 1996 I moved to middle Tennessee. I was only suppose to be here 3 years, the standard length of contracts back then. But a funny thing happened along the road of life. I started raising kids and thought to myself; Where would I rather my children grow up? Miami? L.A.? Chicago? Great News Markets, but you need a bullet proof vest and a tactical evacuation plan for every kindergartner. So for the last quarter century, Nashville has been my home. I’ve seen the Titans move in. I’ve covered the Predators arrival. I’ve seen the transformation to the IT CITY. I’ll never forget my first day at Channel 2. It was February 1996. I arrived in a newsroom that is much different than today. We use to have the anchor desk in the middle of the newsroom. I never understood who thought that was a good idea. The anchors were trying to do their jobs, and read the news, and interview people and all around them people were carrying on, cutting up and making noise. It seemed counter productive. Now we have a million dollar studio that looks as good as anything you’d see on the Networks. Back in 1996, Anne Holt and Bob Mueller and Neil Orne and Vicky Hansen did the broadcast right next to my desk. Scanners blaring and phones ringing and people just being people. I remember Victoria Hansen turning to the group during a commercial break and scolding everyone, reminding them that there was a live newscast going on. Ah, those were the days. Remember TURKO? Chunky white dude, pony tail, big forehead. IT AIN’T RIGHT! It was his shtick. He was our consumer reporter. IT AIN’T RIGHT! He screamed that once when I wasn’t ready for it. I almost dropped a full cup of coffee. So back to that cold February day in 1996. I was uneasy and unsure. I had that first day on the job blues. I didn’t know where the bathroom was, or a stapler or how they did anything at this station. Before I could even get my bearings at 8:30 am, My Assignment Editor screams, “Hey new guy.” I point to myself, while looking around. Yep, she’s talking to me. “We got a gas leak over on blah blah blah..” Nancy Smith is one of the greatest people on planet Earth. She’s kind, and news sagacious, and always brings snacks. News people love free food. But on this day, my first day, I’m looking at Nancy Smith like she’s from the twilight zone. I looked at her blankly. A gas leak? Really? You hire me to cover a gas leak that surely won’t be a story by the time we get there? It was February, cold as hell, and it’s pouring rain. Murfreesboro Road near Fesslers Lane looks awful. The Drake Motel, Where the Stars Stay hasn’t changed in 24 years. It’s still a wonderful place to watch hookers fight, drug dealers yell, and for Metro cops to park and write their reports. OK. So I’m off to a gas leak, with a photog named Barry Cross. A good ole boy from Maury County. Barry was a good photog, but he was a better hunter and fisherman. He got out of this crazy business and is now the spokesperson for TWRA. By the time we get to the gas leak, guess what? It’s over. “Come back to the station,” Nancy says. “You’re going to Clarksville with Al Devine” OK, I thought. I don’t know Al Devine. I don’t know Clarksville. All I know is I am already wet and cold and it’s only 8:45 am. Suddenly I’m in a boxy News car with a News God, named Al Devine. Al is a legendary camera man who began his career in the late 70’s at channel 4. If there was a best story at the bar contest, he’d be the blue ribbon champ. From driving 100 mph to Memphis the day Elvis died, to blowing out 2 tires the day the F-14 crashed into a house in Antioch. Al is a legend. It’s in his blood. Al’s father, Ott Devine started with WSM Nashville as an announcer in 1935 and then managed the Grand Ole Opry. He literally told Elvis he wasn’t right for the gig. Can you imagine? So Al and I travel to Clarksville Tennessee on this cold, rainy day. I-24 isn’t exactly a stretch of beauty and I’m wondering what I may have gotten myself into. Things get more appetizing as we get to the story. Apparently a car traveling too fast has launched into a Waffle House. Several people were killed. It happened over the weekend, but as is often the case, weekend news crews are thin and nobody covered this disaster. So 3 days later we are in Clarksville hunting for clues. I don’t remember most of the details, but Al says, That’s the day he found out how relentless I am. That’s a badge of honor coming from this News savant. When asked to elaborate, Al will tell the story of how we found one of the victim’s addresses. It was on this hill in a very remote location. We climbed the steps of this rickety old house. I banged on the door and it opened, as if by spirits. Both Al and I were nervous. I pushed the door open and peered into the home. It’s dark as night inside. The air is cold and stagnant. There is no apparent movement or life. “HELLO!” I shout into the void. A moment later we hear a muffled reply. “WHO THERE?” “Channel 2 News. Can we talk to about that accident at the Waffle House?” “COME IN,” the voice screams from the back of the home. I look at Al and see the reservation in his face. If you want News, you gotta go and get news. And the news focus of this particular moment is somewhere in the enigmatic darkness of this dwelling. I step into the front room. It’s pitch black. The only light is coming from the front door that is now wide open. “Hello,” I yell again. I notice dust on the back of chairs and accumulating on the frames of old black and white photos on the wall. “BACK HERE,” The voice of a man yells from down a long corridor. Al gives me a look. He doesn’t say anything, but his grizzled news face is twisted like a pretzel. I smile slightly and we walk down a hallway. It is dark and the carpet is worn. The floor boards creak with every step into this foreboding passage way. As we near the end of the hallway, I remember seeing a flickering orange light coming from a room. It’s all very odd and a little unnerving. I take a deep breath and enter the room. It’s then that I see an old black man with bright blue eyes. The man in his 70’s has snow white hair and leather hard skin. But those bright blue eyes are haunting and memorable. They are like wolf eyes peering at me from the dark. The man is seated on his bed and staring at us with a blank gaze. The room is illuminated by a single candle that is burning in a skull. It’s not a reassuring image, but I don’t dwell on it, pretending that everyone has a room illuminated by a skull candle. “hello sir,” I say, introducing ourselves. His voice is muddy and thick from decades of smoking unfiltered cigarettes. I see snuffed out cigarette butts overflowing a nearby ashtray. I quickly come to determine that the man before me is blind. I suddenly realize that what is dark to me, simply is to him. Why a candle is burning inside a skull is a question that Al and I laugh about to this day. As it turned out, the man was related to the victims and was a wealth of knowledge. That moment of intrepid discovery is the difference between a shot of a broken building and a story about people who were loved and lost their lives. Days later, Al, who is still a great friend of mine tells me that I am one relentless SOB. He tells me he was not comfortable heading back into the home, yet he knew I was going with or without him. I’ve often thought about Al’s words. News lurks in many places. Sometimes its in plain site. Sometimes you have to hunt for it by the light of a skull. I have seen many co-workers come and go over my 5 decades in news. It wears on you. It beats you down. The constant grind to find a story. It is relentless, just like that primal cold that pushes out of the Grand Teton Mountains into Wyoming and Idaho. But I still look forward to the next day, the next story. I like telling stories and helping my community. That’s why I like this picture of me bungee jumping. This is the early 90’s in Greenville, N.C. I’m doing a live shot at the fair and for some reason, on live TV, I jumped off a platform. To me, this is my news life. Step off the ledge and don’t hold back. If you’re lucky and if the Gods of news are smiling upon you, the cord will break your fall and you’ll move on to tell another story another day. Life’s Crazy™ |